Throughout many different hospitals in the world, there are Right to Die programs that allow terminally ill individuals to willingly end their lives (with the help of a doctor). This remains true in Orange County, California, in which a State Senator, Catherine Blakespear, wants to open this Right to Die program to patients who are in the early stages of dementia.

This proposal has sparked a debate on how much dementia affects patients’ self-awareness.

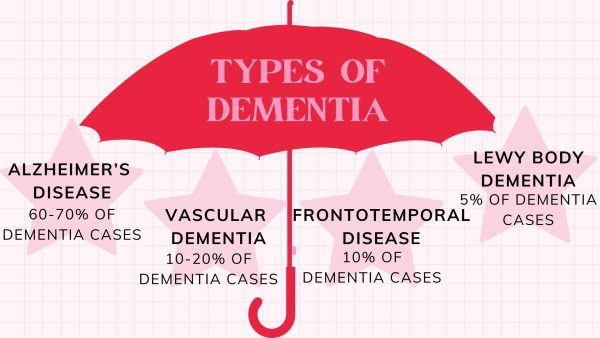

Dementia is a cognitive disorder that is most commonly caused by Alzheimer’s. It is also an umbrella term for other diseases that mess with an individual’s cognitive capabilities.

Knowing this, as well as what State Senator Catherine Blakespear is protesting, raises essential questions. Are people with dementia aware of their condition?

Many individuals who have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, better recognized as dementia, immediately refute their diagnosis, and some can’t even comprehend it. Individuals with dementia may not be able to acknowledge their diagnosis, raising questions about how end-of-life decisions are considered in such cases

Supporters argue that individuals should have a choice over their end-of-life decisions, even when facing cognitive decline. The British Medical Journal emphasizes that “people should be able to exercise choice over their own lives which should include how and when they die, when death is imminent.” This perspective underscores the importance of personal choice in maintaining dignity during the dying process. Jason Barber, who lives with dementia, believes that he and many others should be able to decide how their end is dealt with.

“Death with dignity is a human right: to retain control until the very end and, if the quality of your life is too poor, to decide to end your suffering.” His viewpoint reflects the desire for individuals to have control over their fate, especially after witnessing extended suffering due to degenerative diseases,” Jason explains.

Conversely, critics raise ethical concerns about extending such programs to dementia patients. Dr. Lucy Thomas, a palliative care doctor, cautions that proposed assisted dying bills may not fully consider the complexities observed in other countries’ practices (theguardian.com).

In a case reported by The Wall Street Journal, Lynne Chesley, who had a degenerative disease, specified in her living will that she did not want life-sustaining treatments. Despite this, family disagreements led to her being kept on a feeding tube for over three years. The Oklahoma Supreme Court eventually ruled to honor her advance directive. This situation underscores the critical importance of clearly drafting living wills, selecting a reliable healthcare proxy, and ensuring that these directives are accessible to both family members and medical providers (wsj.com).