Disclaimer: This article is an opinion piece. Any views or opinions represented in this piece are personal and belong solely to the article author and are not endorsed or representative of The Academy Chronicle, Mt. SAC ECA, or the West Covina Unified School District.

Ever since I was little, I could always recall seeing myself on the big screen, and when I say on the big screen, I mean my reflection on my grandma’s TV. I grew up watching shows like Barney, He-Man, and Being Ian and rewatched movies like The Parent Trap, Spy Kids, and every Disney movie ever created. As I grew up, though, I realized how women were often sexualized in all forms of media, whether it was seeing a girl dressed in revealing clothing or leaning into particular fantasies from the films and TV shows that I watched growing up to the magazines I would see in supermarkets and barber shops.

So, at the ripe age of 12, I decided to do what my mama taught me: research. After about 2 minutes of looking online, I discovered the term “the male gaze.” British film theorist Laura Mulvey popularized the term in her 1973 essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, explaining how the “male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly.” Mulvey further explained by saying that the woman is a “spectacle,” and the man is “the bearer of the look.” And while this may seem somewhat harmless, it is detrimental to our society.

The male gaze conditions women to adhere to this patriarchal concept of how women should look and behave, influencing them into subservient roles to please male spectators, emphasizing physical appearance, and placing female empowerment into a secondary position below male sexual desires.

Sociology and criminology professor at Cal Poly Pomona, Dr. Caryn Gerstenberger, explains further, “Media, of course, can’t tell people how to think. But it can reflect, like a funhouse mirror, a distorted reality that many people come to accept without even realizing it.”

Even as I am writing this, in the corner of a Barnes & Noble cafe, eating Kraft mac n cheese in my dad’s sweatpants and T-shirt, secretly watching Josh Hutcherson edits on my phone, there have been countless teenage boys and older men checking me out rather than the thousands of books in the store. I am sick and tired of people emphasizing my physical appearance over what I can bring to the table. And I am sick and tired of seeing females being oversexualized and neglected on the big screen just to satisfy a particular male audience.

So today, let us discuss the continuation of the male gaze in media, how it affects the portrayal of women, and the importance of changing the future of TV and film to be more diverse.

More than a piece of plastic.

I am still obsessed with film and continue to rewatch my childhood favorite shows and TV series. Nevertheless, the more I grow, the more genres of film I explore and the more actors I admire. One of my current favorites is the Barbie movie. I know everyone and their grandmother has seen this film, but at the center of it all is a fantastic message: Margot Robbie is a literal goddess. Robbie can play almost every character, from a villain with a personality disorder (Harley Quinn) to an ice skating knee bruiser (Tonya Harding) to a literal plastic doll. I mean, Robbie has won over 30 awards and 130 nominations for a reason! And in her role as Barbie, Robbie showcases Barbie’s significant role in girlhood.

For those of you who have been living under a rock for the past 65 years, Barbara Millicent Roberts, or Barbie, is the classic material girl doll. Introduced on March 9, 1959, Barbie was created by American businesswoman Ruth Handler and manufactured by American toy and entertainment company Mattel.

Drawing By Annika Wotherspoon

Barbie was inspired by Ruth Handler’s daughter, Barbara. After Handler saw Barbara playing with paper dolls and dreaming about what kind of woman she would become, Handler decided there should be a doll on which girls could project their highest aspirations. Soon after, in March 1969, the first Barbie model was displayed at the Toy Fair in New York City. Within her first year on the market, over 300,000 Barbie dolls were sold, and in 2021, over 86 million Barbie dolls were sold.

Being advertised in the “golden age” of marketing, she was purposefully marketed to have consumers continue spending with each new release of Barbie and her accessories. Everything was meant to evolve the Barbie universe, with the house, car, and pets being sold to help build one’s Barbie world. Not to mention, all of her friends and different career choices were opportunities for the brand to expand the marketing of Barbie’s story.

Of course, her franchise would branch into film and TV, including Barbie in a Mermaid Tale, Barbie: Life in the Dreamhouse, and most recently, the Barbie movie.

Fans were excited, to say the least, about this movie. Teaser photos and videos, like one released by The Daily Stardust, show Gosling and Robbie wearing neon yellow rollerblades and knee pads at Venice Beach in California for their iconic “I have all the genitals” scene. Not to mention, the film was directed by Greta Gerwig, who is most famous for directing Ladybird and Little Women and being one of only eight women in Oscar history to be nominated for the Best Director category as of 2024.

However, after the movie’s release, the internet expressed its love for Ken and his “Mojo Dojo Casa House” with an oversized fur coat, screaming “sublime” at the top of his lungs. Moreover, people are drawing most of their attention to Ken, primarily showing their displeasure with how men are perceived in the movie. Some viewers stated that they did not like how the male characters were presented because they were portrayed as “dumb” or “stupid” throughout the film.

And in no way is Gerwig or any of the crew from Barbie trying to turn the world into a male-hating society, but simply following the Barbie blueprint.

The concept of Barbie was created for young children, predominantly young girls, to control the narrative. Barbie celebrates what we associate with femininity or girlhood, so adding aspects of masculinity into the movie doesn’t have the same effect on the movie or push the whole Barbie is the ‘cool’ girl narrative.

However, the funny thing is that people never batted an eye toward Ken until the Barbie movie portrayed him as “an idiot” and distorted how the world sees men.

Even growing up, I rarely made my Ken doll the main character. He was simply a side character, a character to try and make my story move faster. In BarbieLand, the world is not centered around Ken, and there is no rush to make him the main character; he exists outside the spotlight without resentment or dispute. He is an accessory.

This narrative of being the “accessory” or “side character” is all too familiar. Many others, including myself, recognize that how Ken is portrayed in the movie is remarkably similar to what it is like to be a woman in modern society and Hollywood.

‘Just a pair of measurements, not a person,’ like Jayne Mansfield.

In the early days of entertainment and film, female actresses played roles that would reinforce traditional gender norms, like damsels in distress or dumb blondes, and characters lacking depth and complexity, making them exist as plot devices and objects of desire, emphasizing females’ reliance on male characters.

Despite this, modern cinema has begun to challenge traditional gender stereotypes and present more diverse portrayals of women. Nowadays, female characters are depicted as strong, independent, capable individuals with agency and motivation, occupying a wider range of roles beyond the traditional archetypes.

However, women in the entertainment industry are still underrepresented, with fewer opportunities for roles in major productions and limited access to positions of power and influence within the industry. In addition, the prevalence of stereotypes and tropes surrounding female characters still persists, perpetuating unrealistic standards of femininity.

Moreover, society, for many, many years, has never thought of this idea, so when we are faced with the straight, cis-gendered male damsel or men being the dumb blondes, we tend to reject it and call it “unrealistic,” “demeaning,” or use the phrase “the feminists are trying to make us hate men!”

However, that is not the case. “Feminists are not interested in perpetuating a flipped model where men are discriminated against (although, they may play with this idea like in the Barbie movie where Ken is purposefully devalued to make a point),” states Dr. Gerstenberger. “Feminists are just looking for political, social, and economic equality for women… When you are used to having privilege, any challenge can feel like a loss of status. So many people are rebelling more than ever against feminism, which they see as a threat to the status quo.”

Additionally, Gosling has been nominated, won multiple awards, and received enormous attention for his role as Ken, rather than most of his female castmates. Many people express their frustrations and say that this bias towards males in the industry further proves the film’s point.

However, many cast members have expressed their disapproval on social media regarding the lack of awards and nominations that their female cast members and behind-the-scenes staff have received. Also, stating that no recognition for the film would be possible without them.

The absence of women’s voices and perspectives in the film industry extends far beyond the Barbie movie. For years, systemic barriers have limited female filmmakers’ opportunities, and numerous male-centric narratives have made it more difficult for females in this industry to break through. As a result, women’s voices and experiences remain significantly marginalized in film, further continuing the cycle of inequality within the industry.

So many films are made for male viewers by male filmmakers and producers that it is hard to find something made for women by women. Numerous male films, such as Braveheart, are well-known in our society.

Braveheart centers around William Wallace, a Scottish warrior who leads his people in a rebellion against tyrant King Edward I of England in an attempt to free his homeland. While I do love a film that shows off my ancestors—#ScroogeMcDuck, #DavidTennant, #SCOTLANDFOREVER—the film was made by men, for men. The female characters are used as motivational devices and romantic interests for the male lead.

Drawing By Annika Wotherspoon

Meanwhile, in The Godfather, women are supporting roles within the male-dominated world of organized crime, lacking substantial agency or narrative significance beyond their relationships with male characters.

These male-centric narratives reinforce traditional gender roles and stereotypes but also create barriers for female filmmakers seeking to tell their own stories. By catering to a predominantly male audience, the film industry has limited opportunities for female voices and perspectives to be shown and heard. Female filmmakers have found it challenging to gain support and recognition for their work when the industry only seems to care about work made by men.

Not to mention, queer women are depicted through the lens of heterosexual male fantasies in mainstream media, reducing their identities to mere objects of sexual gratification.

Queer women are frequently hypersexualized; this trend memorializes harmful stereotypes about queer women being sexually immoral or mischievous. Such portrayals not only fail to represent the diverse experiences of queer individuals accurately but also contribute to the obliteration of their identities by reducing them to one-dimensional characters whose sole purpose is to fulfill the male gaze.

The sexualization of queer women in media often intersects with other forms of oppression, such as racism and misogyny. Women of color who identify as queer particularly are liable to be hypersexualized and fetishized, facing the double burden of racism and homophobia.

Furthermore, the film industry has a long history of eternalized toxic stereotypes that immensely affected BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) actresses, often forcing them into roles that emphasize sexualization and objectification to achieve success. This trend reflects a broader pattern of systemic racism and sexism within the entertainment industry, where BIPOC women are often limited to roles that prioritize their physical appearance over their talent and humanity.

From the submissive and fetishized “China doll,” the feisty and hot-headed Latina, to the strong, sexy black women, BIPOC actresses are frequently categorized into roles that reinforce harmful stereotypes and preserve the objectification of their bodies.

It is because of these stereotypes that females all over the world have compared themselves to these roles and questioned if they fit into these stereotypes; if not, some try to morph themselves to “fit in” without knowing that they are slowly sexualizing themselves.

And that is what my concern is. We should not have to sexualize or change ourselves in any way to “fit in.” We should be allowed to express ourselves in any way that we want to without having to worry if we fit stereotypes or without having to worry if we represent our minority group or even worrying about being sexualized by random strangers. We should be allowed to be who we are without any strings attached.

So, how do we accomplish that?

#FixingOurGaze

It is crucial for everyone to challenge the dominance of male-centric narratives and promote diversity and representation. By amplifying female voices and perspectives, the industry can create space for a more inclusive range of stories to be heard and valued. We should amplify, support, and encourage female filmmakers with mentorship programs and funding opportunities, which are essential in breaking down the barriers preventing women from fully participating in the industry.

The film industry must also prioritize diversity, inclusion, and representation by actively seeking out and supporting females at all development levels. In order to dismantle systemic racism and sexism within the industry, it must be accompanied by unquestionable actions to address the root causes of inequality.

Additionally, audiences play a crucial role by supporting films prioritizing inclusivity and representation, signaling the demand for more diverse and authentic storytelling to studios and filmmakers. Ultimately, by challenging the harmful tropes perpetuated by movies like Braveheart and The Godfather, the film industry can move towards a future where all voices are heard and valued, regardless of gender.

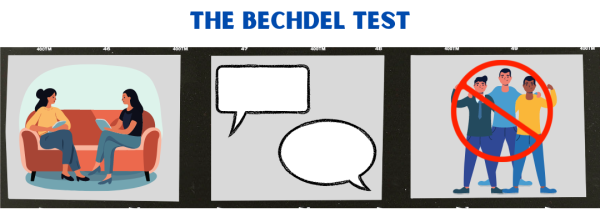

Audiences can also follow the Bechdel Test to ensure they consume inclusive media.

The Bechdel Test has three basic rules:

- The movie must have at least two women.

- The women engage in dialogue together.

- Their discussion must be about something other than a man.

Movies like “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” “The Avengers,” and, shockingly, the entirety of the Lord of the Rings trilogy do not pass the test. However, movies like “Wonder Woman,” “Kill Bill,” Volumes 1 and 2, and Twilight pass the test.

However, this test has inspired many others and helped conclude whether a film or media type is inclusive.

For instance, the DuVernay Test evaluates the representation of BIPOC people in media. This test encourages behind-the-scenes staff, like screenwriters, casting directors, and filmmakers, to include complex POC characters with their plotlines, fully developed personhood, and narrative significance.

Movies that pass the DuVernay Test include:

- “The Color Purple”

- “Daughters of the Dust”

- “Dear White People”

Another test is the Vito Russo Test, which addresses LGBTQ+ representation and highlights the importance of including fully realized, consequential LGBTQ+ characters. For a production to pass the test, they:

- Need at least one character to be identifiably bisexual, lesbian, gay, and/or transgender.

- This character cannot be solely defined by their sexuality or gender identity.

- This character must be integral to the plot, to the extent that removing them would significantly affect the story.

Movies that pass the Vito Russo Test include:

- “The Perks of Being a Wallflower”

- “The Imitation Game”

- “Call Me by Your Name”

These tests are not intended for viewers to determine if a film is feminist, antiracist, or proLGBTQIA+; they are simply a measure of representation.

Even though they do well, it is only the first step. Dr. Gerstenberger stated,” Don’t get me wrong, [the tests are] a great first step. However, we need to move beyond this. We need multidimensional characters that are centered in the story and the plot. I think we are on the right track, but Hollywood moves slowly… I think these tests are important. Yes, I think we should keep measuring these things. But this is [only the] first step.”

Ultimately, by breaking free from the confines of male-centric storytelling, the film industry can create a more vibrant and inclusive cinematic landscape that reflects the diversity of human experiences.

Conclusion

Childhood TV shows and movies hold a special place in our hearts. However, as we grow older and become more aware of societal issues, we realize the media’s impact on our beliefs and values. The male gaze is a destructive concept that has existed in the media for far too long. TV and film have the power to shape our perspectives and influence our actions, and it is up to us to rewrite the path that has already been laid out for us. By understanding the concept of the male gaze and its impact on the portrayal of women, we can actively seek out and support media that promote diversity and depict women in empowering and non-stereotypical roles.